Welcome to All About Bea, a six-part series of posts exploring the life and times of the one and only Bea Arthur! In Part 1 – Beginnings, I explored Bea’s early life and career.

Someone once accused me of trying to turn the sitcom into an art form, and I really believe that’s what I was trying to do.

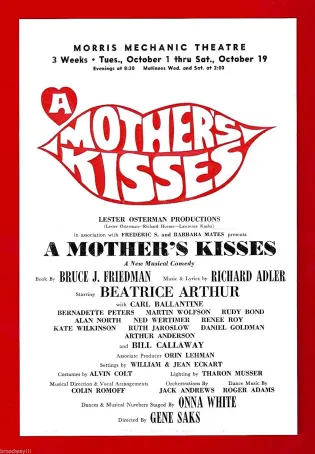

In 1968, following the success of Mame on Broadway, Bea and Gene decided to work together again on a new musical adaptation of the novel, A Mother’s Kisses, by Bruce Jay Friedman. It was billed as Bea’s big break as the leading lady in the role of Meg, an overbearing mother who tries to help her son get into college. It featured music and lyrics by Richard Adler and even co-starred a young Bernadette Peters. Perhaps it was something like the “sophomore slump” because the effort was a resounding flop. The show didn’t do well in New Haven previews and moved on to Baltimore. It was slated for Broadway after revisions but never made it. The character of Meg was described as “crass” and “insensitive” in a Baltimore Sun article about the musical from this time in which Gene also remarked that “there’s a strong natural feeling among people that they don’t want to see a woman like Meg on the stage.” It seems as though the adaptation probably would’ve worked better as a play, and Gene went on to direct other successful Broadway plays while Bea took a break for a few years.

In 1968, following the success of Mame on Broadway, Bea and Gene decided to work together again on a new musical adaptation of the novel, A Mother’s Kisses, by Bruce Jay Friedman. It was billed as Bea’s big break as the leading lady in the role of Meg, an overbearing mother who tries to help her son get into college. It featured music and lyrics by Richard Adler and even co-starred a young Bernadette Peters. Perhaps it was something like the “sophomore slump” because the effort was a resounding flop. The show didn’t do well in New Haven previews and moved on to Baltimore. It was slated for Broadway after revisions but never made it. The character of Meg was described as “crass” and “insensitive” in a Baltimore Sun article about the musical from this time in which Gene also remarked that “there’s a strong natural feeling among people that they don’t want to see a woman like Meg on the stage.” It seems as though the adaptation probably would’ve worked better as a play, and Gene went on to direct other successful Broadway plays while Bea took a break for a few years.

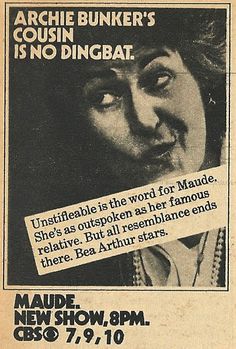

In the early 1970’s an old friend called Bea with a new opportunity. Norman Lear had first seen Bea in the Shoestring Revue in 1955 and admired her talent, particularly her performance of the song “Garbage.” In 1959, he had invited her to appear on the George Gobel Show and they remained friends over the years. Finally, he had the perfect role for her on his hit sitcom, All In the Family. The show was known for its main character, Archie Bunker, a “lovable bigot” who wasn’t shy about sharing his narrow-minded views about life and society. Lear cast Bea as Maude Findlay, cousin to Archie’s wife, Edith. She appeared in two episodes as a liberal foe to Archie with a sharp wit to match. The second episode has the Bunkers visiting for a family wedding and was the backdoor pilot for Maude’s spinoff show. She was a hit with audiences, and Maude premiered on CBS on September 12, 1972.

It was a difficult decision to make–meaning whether I even wanted to do a series. And it was even more difficult when it was decided that Maude would be shot in Hollywood rather than in New York. But Maude had such appeal for me that I couldn’t turn her down.

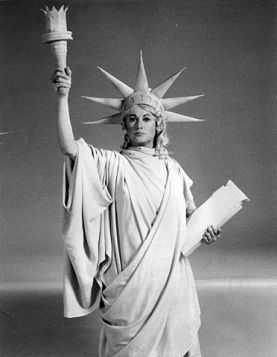

The show’s opening credits feature a rollicking, memorable theme song about historical women including Lady Godiva, Joan of Arc, and Betsy Ross, that ends with “and then there’s Maude” as she opens the front door to her home in the town of Tuckahoe, New York. Maude is the only one shown in the intro clips, but the other characters round out the stellar cast. Bill Macy plays Walter, Maude’s fourth husband, and Adrienne Barbeau plays her daughter, Carol, who is also divorced and living back at home with her son, Phillip. A very familiar face to Golden Girls fans, Rue McClanahan, plays Maude’s friend and neighbor, Vivian. The fantastic Esther Rolle also plays Florida, the no nonsense housekeeper, in the first season. Rolle was a hit, too, and soon got her own spin-off, Good Times. The series featured two other housekeepers as well as another neighbor, Arthur, who is Maude’s conservative counterpart.

In Prime-Time Feminism: Television, Media Culture, and the Women’s Movement Since 1970, author Bonnie J. Dow describes the liberal focus of the show as being “represented by large doses of explicit feminist rhetoric emanating both from Maude and her daughter, Carol.” Indeed, the character of Maude is endlessly discussed but, like all successful and enduring sitcoms, it’s the ensemble that truly makes the show. Maude may suffer no fools but Carol and Walter, and especially Florida, don’t take any of her guff, either. Unlike other mother and daughter sitcom relationships, Maude and Carol are always shown as equals. This is established in the first episode of the series, “Maude’s Problem,” when it’s revealed that Carol is seeing a psychiatrist to sort out her feelings and resentments towards her mother. Maude is forced to confront herself, and the two are friends again by the end. In fact, many episodes of the show depict this dynamic between them as a way to portray Carol as the more modern woman of the two.

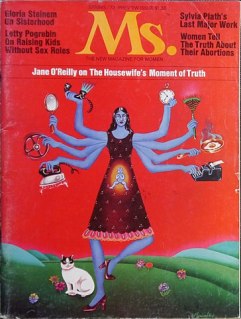

News articles from the time of the show’s first season often focused on the differences between Bea and her character. In interviews highlighting the show’s premiere Bea said, “No, no, don’t call me Ms. I don’t go along with this liberation thing. Liberation from what?” As it happens, Ms. Magazine, co-founded by Gloria Steinem and Dorothy Pitman Hughes, began regular publication in July of 1972. Both Ms. and Maude were part of the second-wave feminist movement, even if Bea herself didn’t identify as such. She had always been happy as a wife and mother, which is completely valid. I think she’s a great example of a woman who always sought balance in her life between home and career. Since the early 1960’s feminists had begun to fight for greater equality for women, particularly in regards to reproductive rights. The series’ most well known episode, “Maude’s Dilemma,” even starts with Carol and Florida discussing “this new designation, Ms., pronounced miz.” This groundbreaking, two part episode deal’s with Maude’s decision, at the age of 47, to have an abortion.

Written by none other than Susan Harris, the script originally dealt with Vivian being pregnant, but Lear believed the story should focus on Maude with a greater emphasis on the topic of abortion. Both parts of the episode are skillfully written, with the first being a great showcase for Bea’s comedic talent and physical comedy skills as everyone learns that she’s pregnant. It’s Carol who first tells Maude that she has a choice. Abortion was made legal in New York that same year, although Roe v. Wade would not be passed until 1973, legalizing abortion throughout the United States. Carol tells her later in the first part, “We’re free! We finally have the right to decide what to do with our own bodies!” Harris’ writing and pacing of the first episode is masterful, especially in the way that the word abortion isn’t used for the first time until near the end of the episode. The second part also balances humor with emotion as Maude begins to realize that she truly doesn’t want to be a mother again. It also includes a “B” story line in which Walter grapples with deciding to get a vasectomy, showing that men also have a stake in preventing pregnancy. In the end, Maude decides to go ahead with the abortion.

CBS decided to rerun the episodes in 1973 after some controversy had built up following the Roe v. Wade decision. Forty affiliate stations refused to re-air the episodes, and CBS received more than 17,000 letters in response. Viewers also wrote in to local newspapers across the country to share their opinions. Regarding the backlash, Bea said that she was “appalled” and “resented…the accusation of our using abortion in a humorous manner.” While the episode is certainly humorous, it never crosses the line into treating the procedure itself as a joke. Bea also noted that she was “for the rights of women being able to decide whether they want to bear a child or not.” The episode received huge ratings at the time, and “Maude’s Dilemma” still remains unmatched for the way that it featured not just the topic of abortion but the real emotions surrounding the decision on television.

While Maude was still in its first season, Bea also began working on the film adaptation of Mame, reprising her role as Vera Charles again under the direction of her husband, Gene. Unfortunately, this version stars Lucille Ball instead of Angela Lansbury in the title role. Ball had neither the dancing nor the singing skills of Lansbury by this time in her career, and the film was not a success. In her Television Academy Foundation interview, Bea called the experience “a tremendous embarrassment” and noted that “having worked with Angela” previously on Broadway that the film was “very difficult” to make. She says that Lucille Ball was charming and wonderful to work with but shares that she “just didn’t feel she was right for the part” of Mame. For her part, Bea’s performance as Vera is great, just as it was on Broadway, but the chemistry that she had with Angela on stage definitely isn’t there in the film. This also marked the last time that Bea and Gene would work together professionally.

Throughout its time on the air Maude continued to address topics that had once been taboo on television. Season two began with episodes that dealt frankly with Walter’s alcoholism, and the couple’s marital conflicts were a frequent topic on many episodes. Season four included the unique episode, “Maude Bares her Soul,” in which Maude is the only character shown delivering a monologue at her psychiatrist’s office. Later in the season, “Maude’s Mood,” another two-part episode, reveals that Maude is bipolar. That season also featured a multi episode story line about Maude’s involvement in politics and her bid for a seat in the New York senate. In season six Maude challenged Arthur and spoke out in support of LGBT people to help save a gay bar that opened in their town. Finally, the series ended with Maude achieving her political dreams and moving with Walter to Washington, D.C. to take over as Congresswoman for a recently deceased friend. The series also included discussions of menopause, Maude’s hysterectomy, fears about aging, financial difficulties, sexual harassment, and other issues that helped change the landscape of television sitcoms.

Bea was nominated many times for an Emmy award for best lead actress in Maude, and she finally won in 1977 for her work on the fifth season of the show. In true Bea fashion, she remarked that, after waiting so long to win, she didn’t “take the Awards all that seriously” by that point. Although she also said at the start of the sixth season that she loved doing the show, by the time filming wrapped on the “Maude’s Big Move” episodes in 1978 she announced that she, too, was ready to move on. The show ended on a high note, but Bea and Gene also divorced later that same year.

I think Maude’s appeal is that she is a real person. She’s over 40, she’s big, and she’s what I am–as opposed to many of the women in situation comedies who are beautiful, sweet, and charming at all times.

In many ways, Maude was so successful precisely because of the political climate in the United States at the time. The end of the Vietnam War and Watergate are just some of the other events that made this era such a turbulent and landmark time in history. Maude also provided a mirror for the liberal viewpoints that became more mainstream throughout the series’ run. It was also, simply put, extremely funny. Lear knew what he was doing when he cast Bea as Maude, and her talents were always on display to their full advantage. The interactions between Maude and the other characters, particularly Vivian and Walter, are still some of the funniest and smartest writing you’ll see on a sitcom. Maude’s withering retort, “God’ll get you for that, Walter,” has become the show’s most memorable catchphrase.

The show also represented a turning point for women in the 1970’s. Keep in mind that, prior to the Equal Credit Opportunity Act of 1974, women still could not apply for their own credit cards, among other things. Maude’s brand of feminism exemplified the complicated reality for women at the time. Dow further notes that “Maude…represented a privileged and protected feminism. Supported by her husband’s business, her controversial views could not lead her to lose her job. Given her domestic servants, she was hardly an oppressed household drudge. Older, married to a man who apparently loved her for what she was, she had no fear of being perceived as a man-hater or a woman whose politics would impede her love life. Maude could announce her views views daily without fear of repercussions.” So while Maude’s brashness took place largely in the protected space of her middle class home, it nonetheless represents the shifts in power for women that occurred during the decade. The show overall also represented a responsive exploration of Betty Friedan’s influential work from the early 1960’s, The Feminine Mystique, by portraying a woman who wanted more out of life and saw that she got it. If you’re interested in reading more, Lives Together/Worlds Apart: Mothers and Daughters in Popular Culture, by Suzanna Danuta Walters, also provides an excellent analysis of the show.

Maude maintained a top-ten Nielsen rating until its last two seasons and appeared on the cover of TV Guide five times. While not quite a record for cover appearances, it’s still impressive for a sitcom than ran for six seasons and reflects the show’s popularity at the time. Funnily enough, the person who holds the record for most TV Guide cover appearances is none other than Lucille Ball. Lear also had to fight to get the show into syndication, enlisting the help of Betty Ford, who was a huge fan, to get it picked up. Maude hasn’t enjoyed the same long lasting success in re-runs as Good Times, The Jeffersons (also an All In the Family spin off), and other 1970’s sitcoms, but its importance as a show that featured an outspoken, politically active woman in the lead role continues to be influential.

Before Maude, Bea was primarily known for her work on the stage and Broadway, but Maude made her a household name. It’s clear that Bea also really enjoyed playing Maude and being a part of something so significant. Interestingly, by the show’s end in 1978, Bea was more willing to discuss the ways she was similar to Maude, a departure from how she felt back in 1972.

I adore Maude. . . . I have some of her qualities. . . . I may not be as politically active. But if something bugs me and I feel something needs attention, I give it. I’m very vocal about things that move me.

Bea never identified as a feminist and she still didn’t see herself as being a part of the “women’s lib movement” even though she’d spent six years portraying a character who very much represented those things, but I think Maude helped to expand how she viewed herself.

The 1970’s was definitely a time of highs and lows for Bea. She was never one to rest for long, though, especially when creative and interesting projects were on the horizon. In the next installment of All About Bea we’ll pick up with something completely different, in a galaxy far, far away.

Fabulous post

LikeLike

Thanks so much!

LikeLike

Enjoyed the “golden girls”

LikeLike

I love this series! Just came across your blog and I’m loving it. I’ve always wanted to know more about Bea and her career and you’re giving a great overview of her life so far.

LikeLike

Thank you so much!! ❤

LikeLike

Pingback: Fashion As Tension In Dorothy’s New Friend – The Golden Girls Fashion Corner

Pingback: Happy Birthday, Bea Arthur! – The Golden Girls Fashion Corner

Would love to see part 3:)

LikeLike

Thank you! Me, too! Haha I hope to get all of these posts finished at some point!

LikeLike

Pingback: Tattle Tales: Tabloids and The Golden Girls – The Golden Girls Fashion Corner

Pingback: Bea Arthur Hosts An Evening at the Improv – The Golden Girls Fashion Corner

I m loving everything you said about Bea…. Can t wait to read part 3

from Italy

LikeLike

Grazie! 🙂 Stay tuned!

LikeLike